Here's a more constructive variation on my previous post. There are been complaints that the new Inspiration mechanic in

D&D 5E is "dissociated," "meta-gaming" that pulls a player out-of-character. How Inspiration does this while the ability to fight without impairment even at 1 HP out of 60 doesn't is a question that never seems to get answered. (The answer, by the way, is that different players occupy different locations on the immersion spectrum and thus lose immersion at different times in response to different mechanics.)

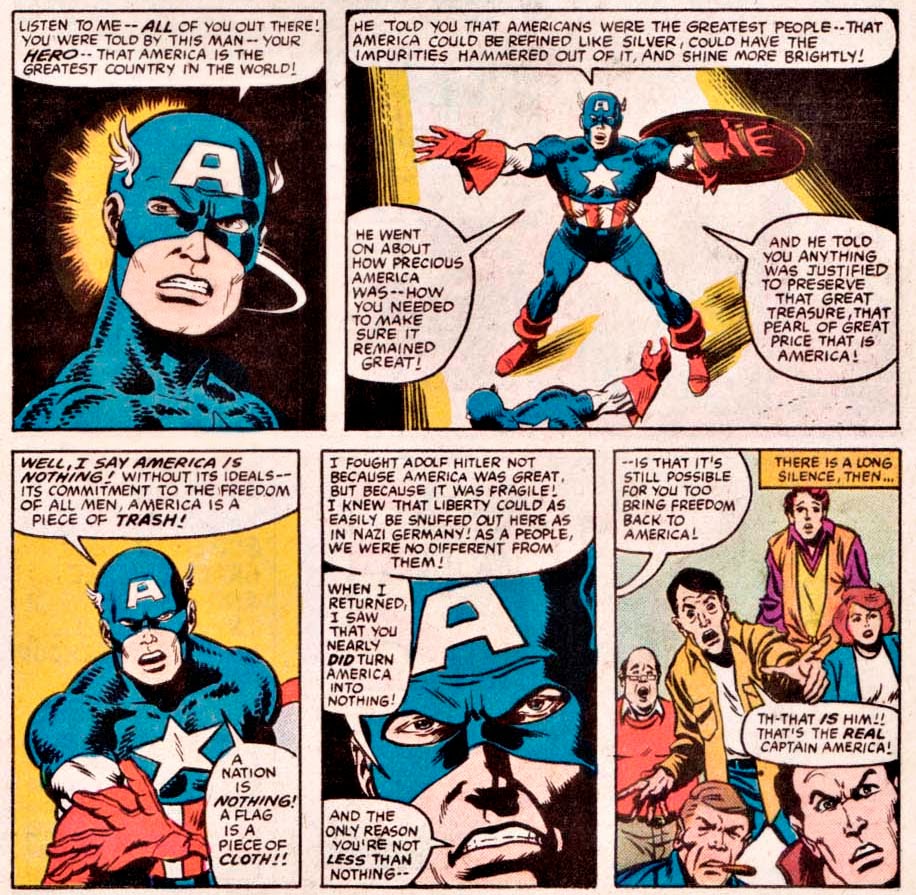

I find that Inspiration perfectly maps onto in-character decision making, and I'm going to use Walt Simonson's

Thor #362 to illustrate what I mean.

The situation is this: Thor has led the forces of Asgard into Hel to rescue the souls of mortals falsely imprisoned there. He's managed to succeed, but at the cost of grievous injuries to his face from Hela's clutches. As the Asgardians withdraw with the rescued souls, Hela uses a technicality to violate the cease-fire between the two sides and sends her undead armies after them. For the Asgardians to escape, someone has to stay behind and hold the Gjallerbru against the dead long enough for the good guys to make it past the boundaries of death. Like the hero he is, Thor states he'll do this. The others protest in vain, and Thor is only stopped from sacrificing himself when Skurge the Executioner, a former enemy of Thor's in the employ of the seductive Enchantress, coldcocks our hero and offers to take his place at the bridge:

In game terms, Skurge is the neutral evil low-Wisdom fighter who's been a pain in Thor's ass for several hundred sessions / issues. Out of nowhere he makes this amazing in-character speech explaining his willingness to die for his former foes' sake. The player of Balder, the lawful good paladin who was resurrected just before the start of Simonson's run, is so impressed by Skurge's player's speech that he grants his Inspiration point to Skurge (as per p. 36 of the

Basic Rules PDF). The actual exchange of the point is right there on the page in panel 6, the moment when Balder hands Skurge his M-16. (The Asgardians are rocking American longarms in this storyline—it's a comics thing.)

This is a perfect example of how a simpatico group of players can make in-character sense of the player-instigated Inspiration trading mechanic. Skurge's speech is precisely the sort of "good roleplaying" the rules mention, and his statement that Balder is the only god to never laugh at him works an in-character explanation of why the point moves from the paladin to the fighter. DM Walt Simonson probably could have just as easily given Skurge's player the point in response to his awesome roleplaying, but Balder's player beat him to the punch.

OK, what about Skurge's expenditure of the point? How is that conceivably in-character? Well, in the first place, I think some people are getting hung up on the term "Inspiration." You could just as easily call the mechanic "Willpower" or "Determination." It's the moment when someone buckles down to get the job done, when their concentration narrows and their range of possibilities expands. Don't assume that it's only a meta-fictional trick of authors in complete control of their characters and plots: I know for a lived fact that my Bond to my family has allowed me to momentarily alter a situation to my favor. I was briefly "inspired" by that trait, and the odds shifted. As a result of such experiences, the expenditure of an Inspiration point seems perfectly in-character to me—especially since the

D&D 5E has taken care to ensure that Inspiration is a binary state (you only ever have one point at the most; you can't stockpile it or store it in some sort of "Inspiration bank").

In Skurge's case, it's his Flaw (his unrequited love for the Enchantress) that motivates his expenditure of the Inspiration point at Gjallerbru:

(Wait for it ... we're getting there ... just wanted to show this awesome page layout: note how the tier 2 panels containing the approaching undead cavalry widen as the bad guys approach Skurge and the reader, and revel in that amazing final tier with the stylized Norse bridge backdrop.)

"As the warriors of death ride hard down upon him ... the Executioner turns his thoughts from the flowing blond hair that always dances before his eyes ... and begins to do the thing he does best! BUDDA BUDDA BUDDA BUDDA KAPOW! KAPOW! BLAM! BLAM! BEYOWWW!" Tier 2, panel 2 is the moment where he spends the Inspiration he got from Balder to whoop undead soldier ass. To me, that expenditure is as in-character as it gets.

Obviously, others may feel differently, may find that even this relatively restrained mechanic (players periodically get a point they may spend to justify gaining advantage) breaks their sense of immersion. I am in no way suggesting that my experiences and tolerances are universal. But I do think this post demonstrates that so-called "dissociation" is not an objective quality of mechanics but a subjective quality of players—and why I'd like to see the term retired in favor of honest discussions of personal gaming preferences and tolerances.

The next two pages of

Thor #362 boil down to Simonson dropping the mike and walking off stage:

(Pardon me while I sit here a spell and contemplate the parallel yet contradictory motions of tiers 2 and 3: tier 2 pulls back away from Skurge, tier 3 zooms in on the M-16's muzzle.)

In the immortal words of the Kool-Aid Man: "OH YEAH!"

What, you thought I was going to let you go without showing all of the greatest death scene in the history of superhero comics?*

* OK, Supergirl's death in Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 is up there too. Props to Marv Wolfman and George Perez for that!